Coronaviruses, one of a variety of

viruses that cause colds, have been making people cough and sneeze seemingly

forever. But occasionally, a new version infects people and causes serious

illness and deaths.

That is happening now with the coronavirus that has killed at least 26 people and sickened at least 900 since it emerged in central China in December. The World Health Organization is monitoring the virus’s spread to see whether it will turn into a global public health emergency (SN: 1/23/20).

Among the ill are two people in the

United States who contracted the virus during travels in China. A Chicago woman

in her 60s is the second U.S. case of the new coronavirus, the Centers for

Disease Control and Prevention confirmed January 24 in a news conference.

Officials are currently monitoring 63

people across 22 states for signs of the pneumonia-like disease, including

fever, cough and other respiratory symptoms. Of those people, 11 have tested

negative for the virus. Two, including the newest case and another

patient in Seattle, tested positive, the CDC reported (SN: 1/21/20).

France reported two cases on January 24

as well, the first in Europe.

Much still remains unknown about the new coronavirus (SN: 1/10/20), which for now is being called 2019 novel coronavirus, or 2019-nCoV. Lessons learned from previous coronavirus outbreaks, including severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS, and Middle East respiratory syndrome, or MERS, may help health officials head off some of the more serious consequences from this virus outbreak.

What are coronaviruses?

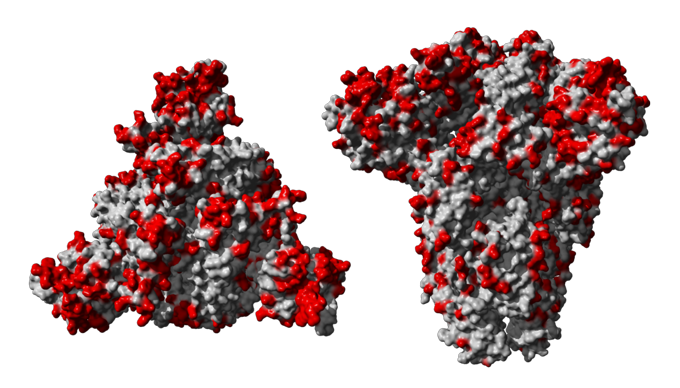

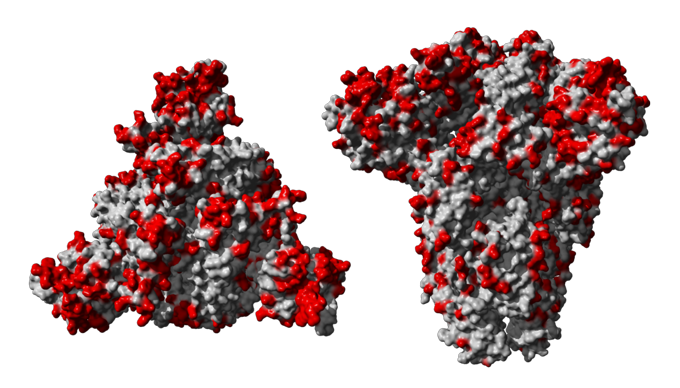

Coronaviruses are round and surrounded

by a halo of spiky proteins, giving them a resemblance to a crown or the sun’s

wispy corona.

Four major categories, or genera, of

coronavirus exist. They’re known by the Greek letters alpha, beta, delta and

gamma. Only alpha and beta coronaviruses are known to infect people. These

viruses spread through the air, and just four types (known as 229E, NL63, OC43

and HKU1) are responsible for about 10 to 30 percent of colds around the world.

What makes a virus a coronavirus is only

loosely enshrined in its DNA. “The coronavirus designation is less about the

genetics and more about the way it appears under a microscope,” says Brent C.

Satterfield, cofounder and chief scientific officer of Co-Diagnostics, a

company based in Salt Lake City and Gujarat, India, that is developing

molecular tests for diagnosing coronavirus infections.

Coronaviruses’ genetic makeup is

composed of RNA, a single-stranded chemical cousin of DNA. Viruses in the

family often aren’t very similar on the genetic level, with some types having

more differences between them than humans have from elephants, Satterfield

says.

The new virus’s proteins are between 70

and 99 percent identical to their counterparts in the SARS virus, says Karla

Satchell, a microbiologist and immunologist at Northwestern University Feinberg

School of Medicine in Chicago.

How dangerous is a coronavirus infection?

Usually coronavirus illnesses are fairly mild, affecting just the upper airway. But the new virus, as well as both SARS and MERS, are different.

Those three types of betacoronaviruses

can latch onto proteins studding the outside of lung cells, and penetrate much

deeper into the airway than cold-causing coronaviruses, says Anthony Fauci,

director of the U.S. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases in

Bethesda, M.D. The 2019 version is “a disease that causes more lung disease

than sniffles,” Fauci says.

Damage to the lungs can make the viruses

deadly. In 2003 and 2004, SARS killed nearly 10 percent of the 8,096 people in

29 countries who fell ill. A total of 774 people died, according to the World

Health Organization.

MERS is even more deadly, claiming about

30 percent of people it infects. Unlike SARS, outbreaks of that virus are still

simmering, Fauci says. Since 2012, MERS has caused 2,494 confirmed cases in 27

countries and killed 858 people.

MERS can spread from person to person,

and some “superspreaders” have passed the virus on to many others. Most

famously, 186 people contracted MERS after one businessman unwittingly brought

the virus to South Korea in 2015 and spread it to others. Another superspreader

who caught MERS from that man passed

the virus to 82 people over just two days while being treated in a hospital

emergency room (SN: 7/8/16).

Right now, 2019-nCoV appears to be less virulent, with about a 4 percent mortality rate. But that number is still a moving target as more cases are diagnosed, Fauci says. As of January 23, the new coronavirus had infected more than 581 people, with about a quarter of those becoming seriously ill, according to the WHO. By January 24, the number of reported infections had risen to at least 900.

An analysis of the illness in the first

41 patients diagnosed with 2019-nCoV from Wuhan, China suggests that the virus

acts similarly to SARS and MERS. Like the other two, 2019-nCoV causes

pneumonia. But unlike those viruses, the new one rarely

produces runny noses or intestinal symptoms, researchers report January 24

in the Lancet. Most of the people

affected in that first group were healthy, with fewer than a third having

chronic medical conditions that could make them more vulnerable to infection.

Where do new coronaviruses come from?

Coronaviruses are zoonotic, meaning they

originate in animals and sometimes leap to humans. The first 2019-nCoV infections

detected in December were in patients who had visited the Huanan seafood market

in Wuhan. The market was closed January 1, but health officials have yet to

determine from which type of animal the virus jumped to humans.

Bats are often thought of as a source of

coronaviruses, but in most cases they don’t pass the virus directly on to

humans. SARS probably first jumped from bats into raccoon dogs or palm civets

before making the leap to humans. All the pieces necessary to re-create SARS

are circulating

among bats, though that virus has not been seen since 2004 (SN: 11/30/17).

MERS, meanwhile, went

from bats to camels before leaping to humans (SN: 2/25/14). A paper published January 22 in the Journal of Medical Virology suggests

that the new coronavirus has components from bat coronaviruses, but that snakes may have

passed the virus to humans. But many virologists are

skeptical that snakes are behind the outbreak (SN: 1/24/20).

How contagious are coronaviruses?

It depends on the coronavirus, but

neither SARS or MERS have been able to sustain human-to-human transmission the

way influenza viruses can, Fauci says. That’s because the viruses haven’t fully

adapted to infect humans, “and maybe they never will,” he says.

Still, “this is a family of viruses that

was formerly just the common cold,” he says. “But now, in the last 18 years,

we’ve had three examples of it jumping species and causing serious disease in

humans.” He and colleagues wrote an article published

January 23 in JAMA to illustrate what

they see as the growing threat from coronaviruses.

In Wuhan, the new coronavirus has been

able to transmit down a chain of up to four people, health officials said. Five

members of a family from Shenzhen, China caught the virus when they visited

infected relatives in Wuhan, researchers report January 24 in the Lancet. Travelers have also carried the

virus from China to at least seven other countries, including the United

States. No human-to-human transmission has yet been reported outside of China,

the WHO said. All of the deaths have also been in that country.

Epidemiologists are frantically

calculating how infectious the new virus is, says Maimuna Majumder, a

computational epidemiologist at Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical

School.

The number that describes how many

people a newly infected person is likely to pass a virus to is called R0,

pronounced R

naught (SN: 5/28/19). SARS, for

instance, had an R0 between two and five, meaning that in a fully

susceptible population an infected person could potentially spread the virus to

two to five others. (Highly contagious measles, in comparison, has a R0

from 12 to 18.)

Estimates for the infectivity of the new

virus range from the WHO’s estimate of 1.4 to 2.5 to a much bigger 3.6 to 4.0

calculation from Jonathan Read of Lancaster University in England and

colleagues. Read’s group estimates that only about

5.1 percent of cases in Wuhan have been identified. The researchers

reported the preliminary results January 24 at medRxiv.org.

That’s probably not because the Chinese

government is covering up how bad the outbreak is, Majumder says. Many people

may have had only mild symptoms or none at all. Those people probably wouldn’t

go to the doctor and get tested for the virus.

Majumder and Harvard colleague Kenneth

Mandl used a different method to calculate R0 for the new virus,

estimating based on cases reported as of January 22 that its transmissibility

falls from

2.0 to 3.3. Their results were posted to SSRN on January 23.

Meanwhile, Christian Althaus and Julien

Riou, both of the University of Bern in Switzerland, posted data to Github

supporting their calculation that the new virus’s infectivity is between 1.4 and 3.8. Each of those

calculations was arrived at using different methods. While they are slightly

different, they overlap, and Majumder says she’s reassured that the numbers are

similar.

Similar infectivity to SARS doesn’t mean

the new virus will spread like that one did.

“Having SARS in [our] history can help

inform some these decisions that we’re going to make now. Back then, we were

less prepared than we are now,” Majumder says.

What treatments are available?

For now, all doctors can do is treat

symptoms of the new disease. Researchers have also developed some experimental

treatments based on SARS and MERS, including antibodies that may help combat

the infections, Fauci says.

Getting samples of the new virus may

allow researchers to develop “monoclonal” antibodies in the lab. Or scientists

may be able to take immune B cells from people who already have recovered from

the virus to produce antibodies to help other infected people.

Some antiviral medications have shown promise in treating MERS, and are being tested for their effectiveness against 2019-nCoV. Experimental vaccines, Facui wrote in JAMA, including some based on RNA, are also in the works.

Erin Garcia de Jesus contributed to reporting of this story.